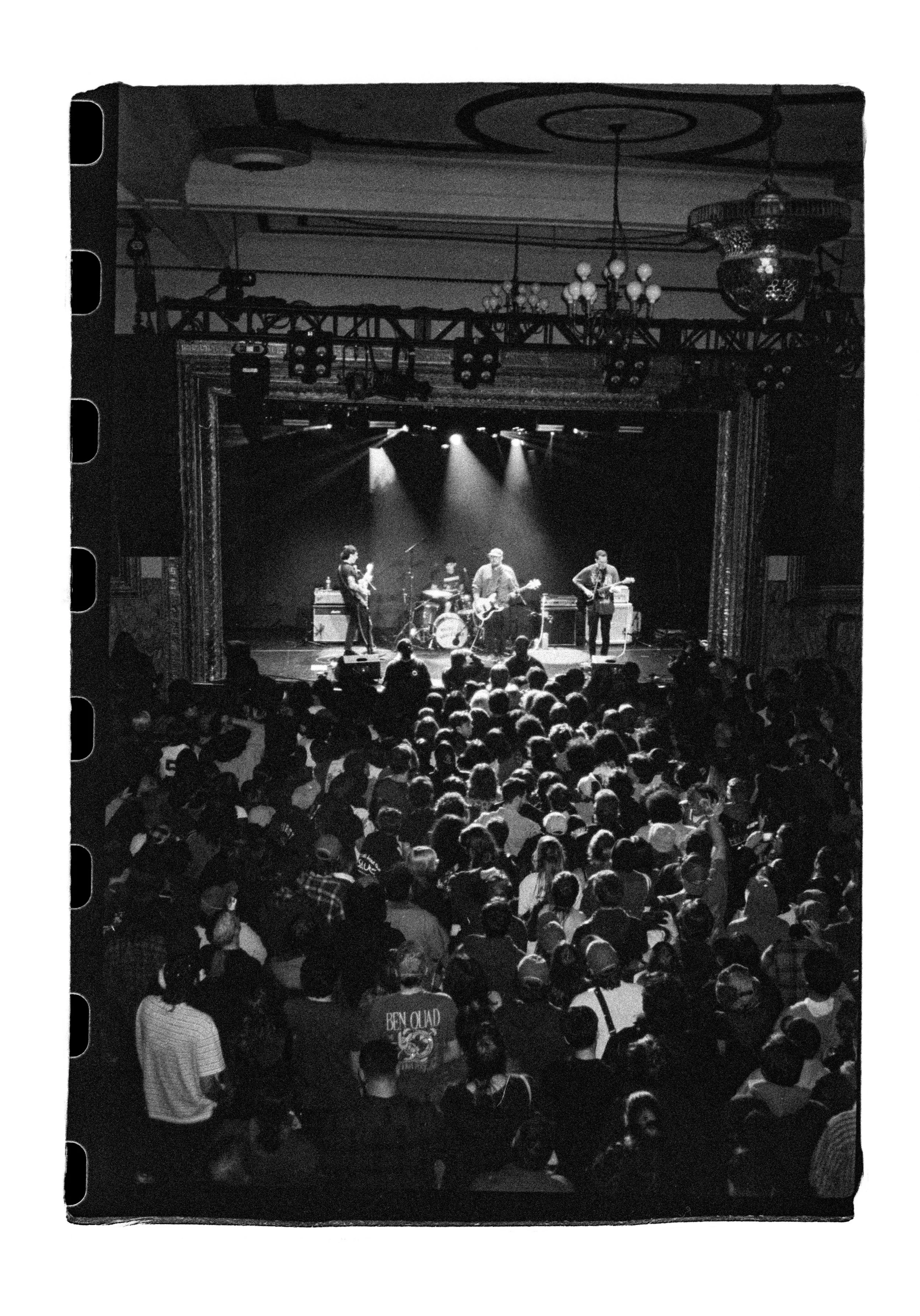

I spent the day with Marietta through the slow hours before their reunion show at Warsaw in New York City, watching soundcheck drift into dinner at a sports bar a few blocks away and then into the long, quiet stretch before doors opened. All afternoon we wondered what the crowd would be like, and the answer came the moment the band stepped onstage, the room erupting instantly.

I spent the night moving through the venue with a handful of cameras, capturing a behind the scenes look of the day while putting together questions for the guys, thinking about how strange and rare it is to watch a band return to something that once meant everything to so many people. Almost a decade later, their return feels less about starting again and more about facing the passage of time and the versions of ourselves that grew in its wake.

You emerged in the scene right as the so called emo revival wave was cresting and collapsing at the same time. Did that tension affect how you understood yourselves as a band, or how you imagined the future of what you were making?

ETHAN: Not really, to be honest. From the time I was introduced to emo, I wanted to be in a band. I was aware of the emo genre having a boom at the time that Marietta formed, but that was mostly a byproduct of being in a band and living and breathing the scene.

EVAN: I think to some extent - our predecessors, including bands like Algernon Cadwallader, Snowing, Hightide Hotel, Street Smart Cyclist, Glocca Morra, etc. - informed how we wrote our music, but our contemporaries, the bands we were frequently playing in basements with, (Girl Scouts, Nicknames, Sovereignties) played a role as well. I had begun to conceptualize Marietta as a “party emo” band, because I think our venues for performance led to certain aspects of our songwriting - i.e., anthems, breakdowns, dance-y parts, moshy parts. As far as the future of Marietta during that time - all I knew was that I wanted to keep playing and writing, and I was definitely interested in leaning more into a “pop” sound, in an effort to make it more palatable to new listeners. I think you can hear this on As it Were.

The Philly DIY era you came up in has been mythologized from every angle. If you strip away the nostalgia and the lore, what was the private reality of that time, the part of the story that never made it into the version people tell now?

ETHAN: I think the version that folks represent now is pretty darn accurate – and a lot of those sentiments continue to be true today. The Philly scene has always been incredibly welcoming, warm, and full of some of the most talented people I have ever met. The scene allowed me to play a show where I met my wife and found my best friends, and that is a situation and circumstance that is not at all unique to me. There are so many similar stories I’ve heard throughout the years, so many people that decided to move to Philly on a whim because they heard about the scene and stayed here, so many bands we toured with that said the Philly shows were the best ones. There is something really special about the scene in Philly and its ability to lift people up and allow them to make cool art.

However, I don’t want to in any way devalue other scenes or places. Wherever you can find your people and can do what you want to do in a safe and supported way, that fuckin’ rocks. Philly just happens to be where I found my place

ANDREW: When I first came to philly I was still mostly listening to pop punk and ska and 90s boom bap. I was kind of oblivious to the importance of a lot of the bands that were swirling all around the Philadelphia scene. To me, the part that I think I lot of people overlook is I think a lot of us packed out these house shows just because they were good hangs. I just wanted to sit on a couch and drink 40s and try to meet people, and house shows were a great place to do that. I didnt want to play in a twinkly emo band. I didnt know what the hell that meant. What I did know was that damn near every friday night there was a rowhome basementfull of 20-somethings screaming along to every word that Stinky Smelly sang- and I wanted to feel that too.

Being in your early twenties is hard, and if I take off the rose glasses I remember a lot of social anxiety in that scene. There were a lot people that I thought for years were cold or too cool or stand-offish, that I later learned were just uncomfortable in their own skin like I was. It’s easy (and fun!) to glamorize it now, but there was plenty of awkwardness & letdown in that era too. I mean- most of us in that scene gravitated towards emo for a reason.

If you look back at the internal world you were writing from during the early days, would you describe it as hopeful, chaotic, fragile, searching, or something more complicated? And when you play those songs now, does the emotional center feel familiar or has it shifted with time?

ETHAN: As I mentioned before, my life now is much different than it was 10 years ago, so there are some lyrics that I can still absolutely tap into what I was experiencing emotionally at the time, and others where I can recognize where I was coming from, but do not feel as emotionally resonant as when I wrote them. At the time, I was broke, my mental health was in a place where I didn’t have the tools to help get through it in a healthy way, I had not met my wife yet or it was during the time when my wife was across the country so I missed her a ton.

Now, I am married to the love of my life, I have regular therapy sessions and take medication for my OCD and anxiety, and I have a stable job that allows me to pursue the creative outlets I enjoy. There are certain lyrics that are very specific to the time where I can identify what I was going through and empathize for that younger version of myself, they just feel more distant thansome of the other stuff I’ve written.

EVAN: Speaking mostly on the songs I wrote for Marietta, I think “searching” is an apt description of my internal world. I wrote those songs between the ages of 19-21, and the term searching can be applied to all aspects of the music I made during that period of time. Lyrically, I was focused on relationships, growing up, and life transitions in general. Musically, I felt like I was learning as I went - how to play in alternate tunings, how to write “emo” music, and how to structure a song according to the “rules” of emo. Prior to Marietta, I don’t think I had a strong musical identity - I was malleable and receptive to any style, and it just so happens that Ethan motivated me to write in the style of emo. If I had never met Ethan, it’s quite possible that my trajectory as a musician would have led me to a different style or scene. Playing the songs now, as I’ve mentioned before, actually helps me to better understand both my history and my aspirations as a musician. And having seen the significant increase in listeners to Marietta, I think I’ve finally accepted what made these songs so impactful for so many people. So, the emotional center of these songs feels very familiar to me - the things I was writing about and the way I wrote songs are part of the broader story of my life as a musician. I certainly spoke from a younger and more impulsive heart, though.

When the band ended in 2015, it felt abrupt from the outside. As you reunited, did any emotional loose ends from that period resurface, and did revisiting the songs force you to confront versions of yourselves you had not thought about in years?

ETHAN: Speaking only for myself, I think there was a degree of insecurity and guilt on my end, both of which are residual feelings from when I left the band. When I decided to leave the band, I wanted the boys to keep going – I didn’t want them to stop just because I wanted to stop. But they (very nicely) didn’t want to move forward without me, so Marietta came to end. Even though I know I made the right decision for myself, I can’t help but feel guilty about that. With that said, once we started practicing again, all those feelings quickly fell away.

EVAN: The reunion of Marietta was a no-brainer for me, but I don’t think it could’ve happened any sooner than this year. Though our disbandment in 2015 was not as abrupt as it felt to our fans, as we had decided to call it quits probably about 4-5 months prior to the announcement, it did feel a little bit like the rug was pulled out from under me. Following Marietta’s breakup, myself, Andrew, and Ben went on to form Narra, which was a punk-influenced departure from the emo sound of Marietta. After Narra broke up in 2018, I was musically adrift for awhile, and I honestly had to do some internal work to kind of rekindle my relationship with performing and songwriting. As some may know, over the past approximately 6 years, I’ve been working on material by myself, and spent the better half of 2025 recording an album which will be released under the name Home Star this coming January. I think if it weren’t for my immersion in Home Star’s music, I would have been less open to a Marietta reunion. It took me some time to integrate that chapter of my musical life into the broader self-view of myself as a “musician” or “artist.” Now though, I am proud of Marietta’s work and value it in the story of me and my guitar.

Coming back to this material after nearly a decade, do the songs feel like they still belong to you, or do they feel like artifacts from another life? Was there a moment in early rehearsals when something clicked and reminded you why Marietta existed in the first place?

ETHAN: They certainly feel like they still belong to me in the sense that I wrote them and I am proud of them, but singing the lyrics again for the first time in 10 years gave me a ton of perspective I was not expecting. I wrote those songs between the age of 20 – 25, so when I sing those lyrics at 35, I realize just how young I was. There are certain aspects of my lyrics that are evergreen to me personally – a decent chunk of the material stems from my mental health, which will always be applicable to my life – but then there are lines that are extremely specific to a place and time. Which is not to say that they don’t resonate with me anymore, it’s just difficult for me to relate to them because so much has changed in my life.

Practicing again felt natural. When we first started practicing again, I felt self-conscious because I have not played in front of other people in 10 years. But then we started joking around and being our usual insufferable selves and things started falling into place quickly. These boys are some of the people I feel most comfortable with in my life, so it was easy to remind myself that when I started playing again.

EVAN: Because it’s been so long since I’ve played or sang these songs, I did feel a certain amount of distance from them initially. Not to mention that most Marietta songs are written in alternate tunings, when I picked up the guitar to relearn the songs, it quite literally felt like speaking another language for some time. Since 2015, every song I’ve written has been in standard tuning - so to return to these old tunings was a really concrete way of returning to an older version of myself as a musician. All of this being said, when we began rehearsing together earlier this year, it felt like we didn’t skip a beat and it all came back to me rather quickly. Being in a basement with my boys playing music together was the reminder I didn’t need, but very much valued, of why Marietta exists at all.

When an old song suddenly feels foreign, do you try to honor the emotional urgency it carried when you first wrote it, or do you allow your current selves to reinterpret its tone and meaning in a way that reflects who you are today?

ETHAN: Just because a song or lyric doesn’t carry the same impact for me that it did before doesn’t mean that is true for everyone else, which is something that has been so damn cool to see over time as more people have found Marietta. For whatever reason – be it streaming, social media, luck – we now have so many more fans than we ever had before, which has introduced a huge amount of people to listen to the songs for the first time and interpret them for themselves. It has been so cool to talk to all the fans and hear their stories and what the band means to them. That has allowed me to look at the songs from new perspectives.

EVAN: Personally, I sink right back into the feeling and emotion of the songs when I play them. Certain songs, musical passages, or lyrics really transport me to a place and time that feels really comfortable. I don’t feel a tension between my past and present self.

ANDREW: It’s a bit of both. The physicality of drumming has always provided a release for me which inherently stirs some emotion. So coming back to these songs it's been pretty easy for me to latch on to some of that and really ride it back to 2013. On the other hand, I'm doing a lot more singing during our live performances now than I ever was able to do back then, and for that element of it I'm definitely drawing from a fresher well. "Look at me, Ma! I'm 32 years old and still in emotional turmoil!"

Now that the reunion shows in October have had time to settle, what were the biggest takeaways for you as a band, either emotionally or creatively, and how are those experiences shaping what Marietta might look like for fans next year?

ETHAN: A big thing I wanted to address going into these shows with Marietta was my confidence level as a musician. Prior to late 2024, I had zero formal training or lessons with guitar. I started playing when I was about 16 and taught myself. I am lucky in that two of my lifelong best friends are unbelievably talented musicians (which are referenced at the end of “Dantooine”), so I was able to learn a lot from them by osmosis. Other than that, I learned on my own – which is not meant to be a brag! It’s to illustrate how much I did not know. I knew some chord shapes, but that was from memorization and guitar tabs, not because I knew music theory. I played in open tunings mostly because they are super pretty and it was easier for me to write riffs to. I never fully felt like a capital M, “Musician”. A lot of that was imposter syndrome, but some of that is because I did not have a fundamental understanding of my instrument.

So, late last year, I started taking guitar lessons for the first time in my life, and not only do I have a better understanding of music in general, but gosh darnit if it didn’t make me fall back in love with guitar. Now I know what each note on fret board is, I know what a triad is, I can do all the scales, I am comfortable with complex chord shapes, I am learning songs that I previously would have cowered from because I didn’t think I could do it. That was a big personal hurdle in terms of doing these shows. I am really happy that I decided to take lessons. Walking up on those stages felt a little less daunting because of it. Which, again, is not required for you to write music! There are so many self-taught musicians that are utterly bonkers at music. This was an obstacle that was important to me to get through, as well as something I always wanted to do.

My transformation in my confidence level as a musician was a big takeaway for me. Going from feeling like I had no right to be playing music to other people to feeling like I belong. That will certainly go a long way for whatever comes next with the band and whatever shape that takes.

EVAN: I’m mostly just filled with gratitude for the opportunity to have played for so many fans who care about Marietta, and really thrilled to have been performing again. It’s a really important part of who I am that I let fall by the wayside for many years as I tended to other important areas of my life, but a part that I intend on honoring going forward.

ANDREW: Our crowds have been so overwhelmingly positive and kind and active as hell. We got in this game to scream gang vocals at & with our friends back in 2012 and it’s heartwarming to hear people at these shows belting our lyrics along with us in the year of our lord 2025.